This was Cannes number three for me, and after a couple of years of never knowing which queue to be in, what my pass meant I could and couldn’t do and generally feeling a little lost, I was ready to take on the festival with a semblance of composure. However, while the practicalities no longer hindered me living the Cannes dream (including, for the first time having actual Cote d’Azur weather), there was plenty to confuse in this years edition. Heelgate in Cannes year of the woman (more on this below), baffling film endings (no spoilers I promise!) and an almost universally confusing set of prizes all converged into one of my most puzzling Cannes.

Most confusing of all was the new ticketing system, which I somehow managed to trick into delivering me with more competition tickets than I had ever been granted before, so my first screening ended up being the much vaunted Tale of Tales in the Palais. Matteo Garone (Reality, Gomorrah) did as many others at this years festival did – ditched his native tongue to deliver an English-language spectacle with an intriguing premise. A portmanteau film with a mighty cast (Salma Hayek, John C. Reilly, Shirley Henderson, Toby Jones) the film is ravishing to look at, but opinion is divided as to whether the film is only as substantial as its meatiest scene (Salma Hayek hungrily devouring a sea serpent heart). As Simon has written, Garrone’s take on his dark subject matter is uneven and at times slight, but I found it an audience-friendly piece, no tto be taken too seriously. A kind of mash up for Game of Thrones and Wild Tales fans, it could have some good commercial prospects for the right distributor.

Next up was Our Little Sister. Hirokazu Kore-eda’s latest was high on a lot of peoples lists and it’s ‘sororamance’ theme was wonderfully explored. Kore-eda’s portrait of this unconventional family is affirming of the structure of familial bonds rather than overtly questioning and I have heard people say the film is a little too saccharine for their tastes. However, Kore-eda’s faultless ability to evoke the intimacy of domestic relationships and indeed their physical worlds is beyond compare. I could almost smell the cherry blossom and taste the plum wine.

Dennis Villeneuve’s Sicario was a very different film that was equally expertly handled. In Prisoners and Enemy, Villeneuve has shown himself able to deftly carry a film with plausibility issues. Here he takes on the war on drugs in a Mexican cartel, and his skills directing taut performances and pacing a twisty thriller are on display again. Brit Emily Blunts performance is intriguing complex. Unlike in many female-fronted thrillers, Blunts ability to match her male counterparts is not articulated by her physical prowess, but rather her moral fortitude. I was reminded of films such as The Silence of the Lambs and Zero Dark Thirty and so was surprised to learn that Villeneuve had faced opposition to having a female lead for the role, with the investors preferring a male lead. Her male counterparts are consistently brilliant: Daniel Kaluuya as her partner, and her alpha male colleagues; Josh Brolin as an infuriatingly cynical official; Benicio Del Toro as a dark and mysterious fixer that seems to have a very personal axe to grind but the film would have been considerably less interesting without the mixture of confusion,vulnerability and haughtiness that Blunt brings to her role.

A hot ticket this year was Yorgos Lanthimos (Dogtooth, Alps) foray into English-language cinema with The Lobster. The synopsis I had read (In a dystopian near future, single people are obliged to find a matching mate in 45 days or are transformed into animals and released into the woods) and the few stills I had seen had made me giddy with excitement and I was ready for magnificence as I took my seat in my 8.30AM screening. Fans of satirical British output such as Black Mirror and Brass Eye will find a lot to like here, and Lanthimos’ conceit is not only a side-swipe at heteronormative behaviour, but also subtly refers to his native country Greece’s financial troubles. For me the film falls slightly short of the richness of its original premise (especially the idea of humans turning into animals), but its cool and cerebral credentials have charmed many critics and almost all the international programmers I met loved it universally, so it’s sure to create a stir when Picturehouse eventually releases it.

Next up in the Palais was Woody Allen’s latest Irrational Man. This is minor Woody Allen at best, with him returning to well trod (and previously, much better worn) themes of the fallacy of intellect and the existential ethics of crime, mining Dostoyevsky and Patricia Highsmith for his narrative. I was taken by the chemistry between Joaquin Phoenix and Emma Stone, but the standout performance was definitely Parker Posey who steals the film from right under their noses.

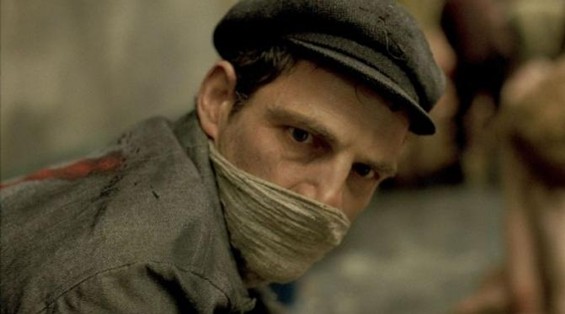

At this point in my competition viewing, I felt due a moment of unexpected discovery, and preferably not an English language one. Enter Son of Saul, the feature debut of Laszlo Nemes, former assistant to Bla Tarrwhich, went on to pick up the Grand Prix. A grimly impressive feat of filmmaking, it is a film that has stayed with me ever since I viewed it and I am only just processing the enormity of the themes covered. Set in 1944 in Auschwitz, it follows Saul Auslander, a Hungarian member of the Sonderkommando, a group of Jewish prisoners forced to administer the horrific day-to-day workings of the death camp. One day while working in one of the crematoriums, Saul finds a boy who he takes for his son and vows to save the boy from being burnt, and tries to find a rabbi to offer the boy a proper burial. A gruelling thriller as well as a deeply compassionate and even-handed treatise on one mans longing for morality in the most amoral of places; this is an astounding piece of cinema that has grown in my estimation ever since I watched it. Artificial Eye have picked up the UK rights and I look forward to sharing the film with our audiences.

My final bit of Competition viewing was an experience that summed up the very best and worst of Cannes. Having secured a ticket for the gala screening of Carol, my most anticipated film from one of my favourite filmmakers (which had already got universal raves) I walked out into the early evening sunshine in my red carpet best feeling pretty lucky to be in Cannes. Carol the film did not disappoint: it’s a wonderfully nuanced portrait of two women whose different lives see them navigate the treacherous waters of romantic love in very different ways. I had recently read the book, but this is a breathtaking piece of art in its own right. Very much Haynes cinematic vision (fans of Mildred Pierce and Far From Heaven will see more references to the photography of Saul Leiter and the paintings of Edward Hopper), it also shows him making quietly subversive points about the personal and public cost of mid-century Sapphic romance. The film could be seen as one of the flashpoints of what Cannes director Thierry Fermaux had dubbed the year of the woman. Opening his festival with a female-directed film (for only the second time) and programming a series of talks and panels on the subject of female representation, Fermaux seemed to be taking on board the yearly criticisms of his auteur-led programming, which has often ignored female filmmakers’ talents.

However, this was the screening where heelgate happened, as a group of women got turned away for not wearing heels. This was also the starriest red carpet I had ever witnessed: walking up the steps of the Palais, it was quite unnerving to watch the ferocious photographers snapping away at the A-list arrivals. Some of these A-listers (Salma Hayek and Aishwarya Rai amongst them) were in Cannes being pretty vocal about the gender inequality in the film industry. Rooney Mara and Cate Blanchett were obviously two of the most wanted that night, and, as I continued to watch them on the screen as I took my seat, I saw that all semblance of ease and poise was almost impossible, as they struggled to keep composed in their too-long gowns and under the glare of hundreds of camera lenses. As they stood in front of the cameras and uncomfortably posed for what felt like an eternity, I couldn’t help thinking that the greatest thing that all the women on that red carpet could have done for gender equality was refuse to have their pictures taken and worn something they could actually walk in without assistance.