Iranian director, screenwriter, photographer and producer Abbas Kiarostami sadly died earlier this year aged 76. One of world cinema’s most vital, sophisticated and mysterious voices, his work channelled Persian culture and spearheaded the Iranian New Wave. Here our Head of Cinemas David Sin remembers his encounters both with Kiarostami himself, and with his illuminating and transcendent cinema.

Its the end of the 1990’s, the end of the century and somewhere near the beginnings of Digital Cinema when I find myself chaperoning a kind of cultural blind date (or was it supposed to be a boxing match?) between the film directors Atom Egoyan and John Maybury at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts.

They meet for the first time when we walk into a packed auditorium. Egoyan, already well established as an auteur on the international scene, is quickly into his stride and characteristically cerebral when talking about the state of cinema; Maybury, fresh from the acclaim at Cannes for his first dramatic feature Love is the Devil, is more reticent at first but soon waxing lyrical about the wider potential of cinema. They both stand up to salute, ironically, the rules and disciplines of the Dogme 95 movement. They mostly agree, discuss facets of cinema at length with elaborate gestures and fascinating insights. I listen but have to do little else. The audience is invited to ask questions and they do,lots. The evening ends, and whilst it would be too much to say that it represented anything other another talk event at the ICA, it is an example of the heightened cinephilia which existed at the turn of the decade.

Six or seven years earlier, I’m trying to put together some public screenings for the Birmingham International Film Festival, briefed to look for important new films from what had been until then considered Third Cinema. I flick through the catalogue of that years Hong Kong Film Festival and find the blurbs for their presentation of a complete retrospective by Abbas Kiarostami. Despite considering myself well versed in World Cinema, I’ve never seen any of the films, not one, dating back to the early 1970’s, for the simple reason that none of them had yet been released in the UK, and this was in the age before the internet made everything available to everyone. Despite this I cannot tear myself away from the write-ups and their accompanying thumbnail images, four or five pages that I read and read over and over again, to make sure that I’m well prepared, know the context, if ever I get the opportunity to see the films. I find even the blurbs about the films, translated from Cantonese into English, fairly hypnotic and wonder why they’ve never been released in the UK, and how I can access them.

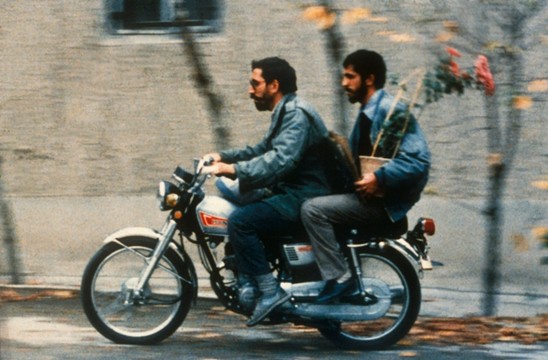

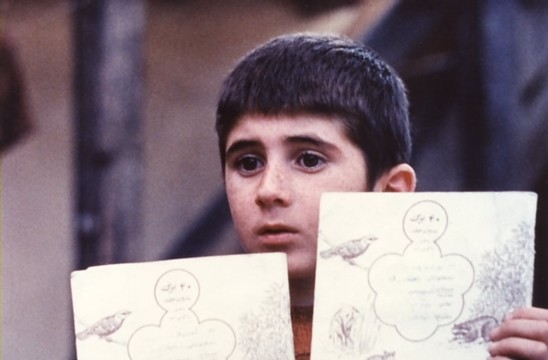

Forward a few years and Kiarostami has won the Palme d’Or at Cannes with Taste of Cherry which has also been released in the UK, along with some of the directors earlier films Through the Olive Trees, Where is the Friends Home?, Life, and Nothing More… and Close-Up. I’m now Director of Cinema at the ICA, the distributor of a couple of these titles and at that time, one of the few cinemas in the UK which regularly exhibited a wider range of films from the Iranian New Wave. Without a zillion pounds to invest in the release of films, my colleagues and I strike some deals to bring to the UK fora few months earlier films by some of the major filmmakers of the time: its a classic curators strategy, to enable audiences to understand the creative development of an artist. One of the first choices is Kiarostamis The Traveller, his first feature length film, made in pre-Revolution Iran but such a blueprint for so many of the films that later emerged from the New Wave. The film proves to be a small hit,like some many of Kiarostamis films, with both critics and the viewing audience. For those few thousand people who saw it in its run at the ICA or on its short tour, I’m sure it felt like a formative experience, like seeing a film for the first time.

During this period, as more of the directors films became available, the experience of seeing each new Kiarostami film was like rediscovering cinema each time, even when viewing them out of chronological order. His films, like cinema, completely blur the lines between reality and fiction,documentary and drama. They appeared fresh and original (even when released years after they were made); they are experimental and formalist, but also funny and full of feeling and compassion for the characters. Each film captures an authenticity in its subjects, themes and settings, providing a vivid view of life in Iran in the 80’s and 90’s whilst also slyly revealing the mechanics of storytelling and acknowledging the illusory nature of cinema. Anyone new to Kiarostamis films released in this period would do well to seek out Close-Up, a dazzling drama which indirectly puts cinema itself on trial.

By the end of the millennium, Kiarostamis films had achieved a kind of global pre-eminence in the film culture, even if he was less well recognised in Iran, and it was the very nature of the films which made them so important to the cinephilia of that era and the development of a World Cinema. His films raised the bar, and developed a whole set of new discourses in cinema which gradually played out at events like the Egoyan/Maybury head to head at the ICA.

Fast forward a few months, and I find myself alongside 50 or so other international guests at the Fajr Film Festival in a wintry Tehran. The majority of the new Iranian films that were all obliged to watch are those deemed exportable by the Republics film agency mostly very culturally-specific genre films, with the occasional gem of experimentation from Abolfazl Jallili or classically honed melodrama from Majid Majidi. After the first couple of days, viewing one after another in the basement of the city’s art museum, were all shepherded back to the main hotel where, that evening, many of the participating filmmakers are gathered. After engaging in polite small talk and trying to work out the best way to tell various filmmakers that their titles wont find an audience in the UK, I’m introduced to Abbas Kiarostami, who’s attending without a film but keen to make connections with curators and industry figures outside Iran. For a superstar of World Cinema, hes modest, self-effacing, and completely approachable. We talk about his forthcoming project and his photography which had never been exhibited in the UK, and he offers to send a copy of his latest treatment which became The Wind Will Carry Us.

Last month, Abbas Kiarostami died in Paris. He leaves behind a magnificent set of films which demand repeated viewing and have the power to turn any regular cinemagoer into a determined cinephile.